Remembering September 11, 1973: The US‑backed Pinochet Coup in Chile

This September marks the 50th anniversary of the US backed coup by Pinochet in Chile. It was one of the heaviest and bloodiest defeats ever suffered by the left and progressive movement in Latin America. There are a number of events being organised in Britain, including in Scotland (full details also below), this year to remember and discuss the Chilean process and coup and links are provided below. (The introductory note is compiled by Dave Kellaway of Anti*Capitalist Resistance in England & Wales.)

The following article is an edited extract of a chapter in a book, Recorded Fragments, by Daniel Bensaid that Resistance Books has translated into English (published in 2020). The book is a transcript of a series of radio interviews Daniel did with the radio station Paris Plurielle in 2008. He discusses the politics behind a series of key dates in 20th Century history. Daniel Bensaïd was born in Toulouse in 1946. He became a leader of the 1968 student movement and subsequently of one of France’s main far left organizations (Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire) and of the Fourth International. He is the author of Marx for our Times, Verso: 2010, Strategies of Resistance, Resistance Books: 2014 and An Impatient Life, Verso: 2015. He died in Paris in 2010.

On 11 September 1973, the Chilean military put a bloody end to the three year reformist experience of the Salvador Allende governments. Augusto Pinochet leader of the armed forces initiated a new cycle of bloody repression and brutal economic liberalism that had started in Bolivia with the 1971 Banzer coup. He was soon followed by other dictatorships in South America such as the one led by General Videla in Argentina in 1976.

The United States, which intervenes throughout South America, has no intention of allowing the people in its backyard to raise their heads against its interests.

Perhaps we should begin by recalling that the 11 September coup, in 1973, and not that of 2001 Twin Towers terrorist attack, was first and foremost an emotional shock. We were transfixed by the news that arrived on the radio from the headquarters of the Presidential Palace, La Moneda, and then by the announcements that gradually came in about the success of the coup d’état. At first we hoped it would not succeed, since another coup d’etat had failed in June three months before, but then we got the news of Allende’s death.

How can such an emotional shock be explained, this had not been our reaction during the bigger bloodbath in 1965 when the Indonesian Communist Party was crushed or more recently with the repression of the Sudanese Communist Party? I believe it is because there was a very strong identification in Europe and Latin America with what was happening in Chile. There was a feeling that this was indeed a new scenario and a possibility, practically a laboratory experiment, which was valid for both Europe and Latin America, in different ways.

So, why was it so important for Europe?

Because we had the impression, partly false I would say today, that we finally had a country that was a reflection of our own reality. Unlike other Latin American countries, there was a strong communist party, there was a socialist party represented or led by Salvador Allende, there was an extreme left of the same generation as ours. Small groups existed like the MAPU(Unitary Popular Action Movement, a Christian current) and MIR, the Movement of the Revolutionary Left, born in 1964-65 under the impulse of the Cuban Revolution. There was an identification with the latter organization, with its militants, with its leaders who were practically of our generation, who had a fairly comparable background. The MIR was formed from two sources: on the one hand inspired by Che Guevara and the Cuban Revolution; on the other hand there was a Trotskyist influence, it must be said, through a great historian of Latin America, Luis Vitale. He was one of the founding fathers of the MIR, even if he was removed from it, or left shortly afterwards. All this in a country where, in the end, Stalinism had never been dominant, including on the left, nor did it have the role that the communist party had in Argentina, for example.

There was a specific factor in Chile, which is one of the difficulties in understanding the situation. The Chilean Socialist Party, even though it called itself socialist, had little to do with European social democracy. It was a party that had been built in the 1930s as a reaction, in opposition to the Stalinisation of the Communist International. So it was a party more to the left of the CP than to the right, so there was a strong sense given to the idea that Chile could give the example of a scenario where the left came to power through elections. This would then be the beginning of a social process of radicalization leading to, or, let’s say, transitioning towards a radical social revolution at a time when, it should also be remembered, the prestige of the Cuban Revolution in Latin America was, if not intact, then at least still very important.

I believe there are still lessons for us about what happened in Chile.

Today, I would be more cautious about this reflection of European realities. I think that, seen from a distance, there was a tendency to underestimate the social relations and the reserves of reaction and conservatism that existed in Chilean society. We saw this a lot in the army because, as was said and repeated at the time, the army had been trained by German instructors on the Prussian army model, which was already not very encouraging. But what’s more, as I’ve seen since then, it’s a country where the Catholic tradition, the conservative Catholic current, is important.

And besides, this was just a starting point. Allende was elected in September-October 1970, in a presidential election, but only with a relative majority of about 37%. For his nomination to be ratified by the Assembly conditions were set. These conditions included two key aspects: no interference with the army and respect for private property. These were the two limits set from the outset by the dominant classes, by the institutions , for accepting Allende’s investiture.

Nevertheless, it is true that the electoral victory raised people’s hopes and sparked a strengthening of the social movements, which culminated in a major electoral victory in the municipal elections of January 1971. I believe that Popular Unity, the left-wing coalition on which Allende was relying at that time, had on this occasion (and only then) an absolute majority in an election.

This obviously gave greater legitimacy to developing the process. So we had an electoral victory, a radicalization, but also a polarization that was initially internal to Chile, which gradually translated into a mobilization of the right, including action on the streets. The landmark date was the lorry drivers’ strike in October 1972. But it should not be thought that it was employee led: it was the employers who organised it. Chile’s long geographical configuration meant that road transport was strategic. So there was this truckers’ strike, therefore, supported by what were called cacerolazos (people banging empty pans) , i.e. protest movements, particularly by middle-class consumers in Santiago. Santiago makes up more than half of the country in terms of population. It constituted a first attempt at destabilization in the autumn of 1972.

At that point, there was finally a debate on the way forward for the Chilean process, which opened up two possibilities in response to the destabilization of the right. The latter was also strongly supported by the United States. We know today with the disclosures of the Condor plan how much and for how long the United States had been involved in the preparation of the coup d’état, through the multinationals but also through American military advisers. So in early 1973, after the warning of the lorry drivers’ strike, there were several options. Either a radicalization of the process, with increased incursions into the private property sector, with radical redistribution measures, wage increases, and so on. All of which were debated. Or on the contrary, and this was the thesis that prevailed, put forward by Vukovik, Minister of Economy and Finance, a member of the Communist Party. The government had to reassure the bourgeoisie and the ruling classes by definitively delimiting the area of public property or social property, and by giving additional guarantees to the military.

The second episode of destabilization was much more dramatic, no longer a corporate strike like that of the lorry drivers, but in June 1973 we saw a first attempt, a dry run for a coup d’état, the so-called tancazo, in which the army, in fact a tank regiment, took to the streets but was neutralized.

I believe that this was the crucial moment. For example, it was the moment when the MIR, which was a small organisation of a few thousand very dynamic militants – we must not overestimate its size, but for Chile it was significant – proposed joining the government, but under certain conditions. After the failure of the first coup d’état, the question arose of forming a government whose centre of gravity would shift to the left, which would take measures to punish or disarm the conspiring military. But what was done was exactly the opposite.

That is to say, between the period of June 1973 and the actual coup d’état of September 11, 1973, there was repression against the movement of soldiers in the barracks, searches to disarm the militants who had accumulated arms in anticipation of resistance to a coup d’état, and then, above all, additional pledges given to the army with the appointment of generals to ministerial posts, including Augusto Pinochet, the future dictator.

So there was a momentum shift, and Miguel Enriquez, the secretary general of the MIR who was assassinated in October 1974, a year later, wrote a text, in this intermediate period between the dry run and the coup d’état, which was called “When were we the strongest? ». I think he was extremely lucid: until August 1973 there were demonstrations by 700,000 demonstrators in Santiago, supporting Allende and responding to the coup d’état. That was indeed the moment when a counteroffensive by the popular movement was possible . On the contrary, the response was a shift to the right of the government alliances and additional pledges given to the military and ruling classes, which in reality meant in the end encouraging the coup d’état.

That is how we were surprised. You referred to the reformism of Salvador Allende but, in the end, compared to our reformists, he was still a giant of the class struggle. If we look at the archive documents today, he still has to be respected.

In the movement of solidarity with Chile, which was very important in the years that followed, 1973, 1974 and 1975, I would say that we were, somewhat sectarian about Allende, who was made into someone responsible for the disastor. That does not change the political problem. It implies respect for the individual, but there is still a conundrum: during the first hours of the coup d’état, he still had national radio, it was still possible to call for a general strike, whereas a call was made in the end for static resistance in the workplaces, and so on. Perhaps it was not possible. Even an organisation like the MIR, which was supposed to be prepared militarily, was caught off guard by the coup. We see this today in Carmen Castillo’s book, An October Day in Santiago or in his film, Santa Fe Street, 2007. They were caught off guard, perhaps in my opinion because they did not imagine such a brutal and massive coup d’état. They imagined the possibility of a coup d’état, but one that would be, in a way, half-baked that would usher in a new period of virtual civil war, with hotbeds of armed resistance in the countryside. Hence the importance they had given – and this is related to the other aspect of the question – to working among the peasants of the Mapuche minority, particularly in the south of the country.

But the coup d’etat was a real sledgehammer blow. They hadn’t really prepared, or even probably envisaged, a scenario of bringing together:

a) the organs of popular power that did exist,

b) the so-called “industrial belt committees (cordones)” that were more or less developed forms of self-organization, mainly in the suburbs of Santiago ;

c) the “communal commandos” in the countryside ;

d) work in the army, and finally

e) in Valparaíso even an embryo of a popular assembly, a kind of local soviet.

Whatever else can be said, all that existed and suggests what could have been possible – but that would have required the will and the strategy. It was another way to respond to the coup d’état, whether in June or September, with a general strike, the disarmament of the army, something akin to an insurrection. It was always risky, but you have to weigh it up against the price of the coup d’état in terms first of all of human lives, of the disappeared, of the tortured. Above all, you have to consider the price in terms of peoples’ living conditions, when we see what Chile is today, after more than thirty years of Pinochet’s dictatorship. It has been a laboratory for liberal policies. It was an historic defeat. If you look at two neighbouring countries, Chile and Argentina, the social movement in Argentina has quickly recovered its fighting spirit after the years of dictatorship, despite the 30,000 people who disappeared. In Chile, the defeat is clearly of a different scope and duration.

I believe that the coup d’état in Chile was the epilogue of the revolutionary ferment that followed the Cuban Revolution for 10-15 years in Latin America. And as you pointed out in the introduction, the dates clearly tell the story: three months before the coup d’état in Chile, I think it was June 1973, there was the coup d’état in Uruguay. In 1971 there was the coup d’état in Bolivia. While the dictatorship had fallen in Argentina, it returned in 1976. But let’s say that symbolically, the killing of Allende, the disappearance of Enriquez and practically the entire leadership of the MIR, closed the cycle initiated by the Cuban Revolution, the OLAS(Latin American Solidarity Organization, meeting in Havana in 1967) conferences, and Che’s expedition to Bolivia in 1966.

Republished from Anti*Capitalist Resistance, 29 August 2023: https://anticapitalistresistance.org/remembering-september-11-1973-the-us-backed-pinochet-coup-in-chile/

Forthcoming events in Scotland

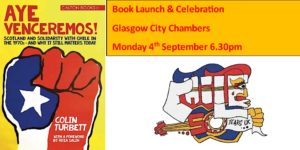

Book Launch – “Aye Venceremos – Scotland and Solidarity with Chile in the 1970s – and why it still matters today.

Monday 4 September @ 18:30 Satinwood Suite, Glasgow City Council, Central Chambers, George Square, Glasgow, G2 1DU

The new book celebrates acts of Chile solidarity in Scotland in the 1970s, including the action by Rolls Royce workers in East Kilbride. It also describes the welcome given to refugees at the time. All this is set against events in Chile before and after the Coup, with eye-witness accounts from some who ended up as political exiles in Scotland. The event is being hosted by City of Glasgow Councillor Roza Salih – herself a Kurdish refugee from Iraq, and a well known campaigner since her school days, for refugee and human rights.

The event will include contributions from Chileans in Scotland, trade unionists and campaigners, as well as the book’s author, Colin Turbett.

For a free ticket via Eventbrite see here > https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/aye-venceremos-book-launch-anniversary-celebration-glasgow-4th-sept-tickets-674133751197

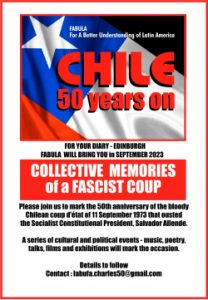

SCOTLAND – COLLECTIVE MEMORIES OF A FASCIST COUP

Monday 4 September – Thursday 21 September

A series of cultural and political events -music, poetry, talks, films and exhibitions to mark the 50th anniversary of the bloody coup d’état of 11 September 1973.

Programme still in development for September 2023 with participation of FABULA ( For A Better Understanding of Latin America ) Full details here: https://chile50years.uk/event/scotland-collective-memories-of-a-fascist-coup/

Programme still in development for September 2023 with participation of FABULA ( For A Better Understanding of Latin America ) Full details here: https://chile50years.uk/event/scotland-collective-memories-of-a-fascist-coup/

For further information email labufa.charles50@gmail.com

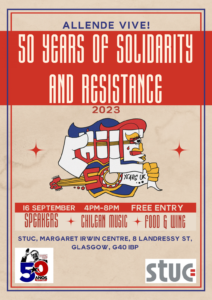

Public event hosted by the Scottish Trades Union Congress (STUC)

Saturday 16 September @ 16:00

STUC, 8 Landressy Street, Bridgeton, GLASGOW, G40 1BP

STUC, 8 Landressy Street, Bridgeton, GLASGOW, G40 1BP