Anti-Fascists Demand Freedom for Zaragoza Six

Jennifer Debs writes for Heckle.Scot about the campaign to free anti-fascist activists in the Spanish state.

If the Scottish independence movement has a sense of internationalism, then events in that blob of disgruntled nations called ‘Spain’ tend to loom largest in our minds. Heckle readers are aware, I’m sure, of how the cause of Catalunya is eagerly identified with the cause of Scotland – one need only attend any independence march to see that evidenced in the Catalan colours among the mass of flags. In a way, this is a kind of Scottish modification of the traditional “philo-hispanism” of the left, our movement’s continuing identification with the history of the Spanish Republic, the international brigades, workers’ power in Barcelona, and the long clandestine struggle against Franco and his regime.

Even so, for all our sympathy with the brave crowds who confronted the Guardia Civil during the 2017 Catalan referendum, our support for persecuted pro-independence politicians, and our disgust at the zombie Francoism of the Spanish government, there are some urgent causes from the peninsula that could do with greater awareness among Scottish workers. Take the case of the Zaragoza Six, a group of anti-fascist activists arrested and imprisoned on trumped-up charges after a protest against the far-right Vox party in 2019.

Just for taking to the streets to oppose the rising threat of fascism in the Spanish state, the Zaragoza Six are facing prison sentences. Theirs has been a years-long battle for freedom since the initial arrests, a story of trials, verdicts, appeals, and yet more trials, with three of the group now having entered prison as of April 16th, and one more set to enter prison on April 24th. These four comrades will each be serving a sentence of four years and nine months, and that on top of heavy fines.

As anti-fascists facing punishment, the cause of the Z6 demands the enthusiastic support of the Scottish left. Not only have we witnessed fascist political organisations making a comeback in the anti-refugee protests at Erskine, but far-right public order and culture war politics lead the way in the Conservative Party, with the government taking aim at refugees, climate protesters, striking workers, Palestine activists and transgender people. The danger is in the streets, but also in the halls of government. The Spanish context, with the role played by both Vox and by state repression, therefore warrants our close attention – our national situations are two facets of a wider phenomenon.

In order to find out more, I reached out to the Z6 campaign to see if I could interview anyone and bring their story to an audience over here. They were happy to speak to Heckle, and so Javitxu Aijon, one of the Six, got in touch with me to speak over a video call. My discussion with Javitxu took place when he was still free, but I am sad to say that as you are reading this now, he is behind bars.

I began by asking Javitxu who the Zaragoza Six are, and about their case. Essentially, Javitxu said, they are just six people who were arrested following a demonstration against a meeting of the far-right Vox party at Zaragoza’s auditorium on 17th January 2019. Just one month prior to the demo, Vox had entered the Andalusian parliament, “so there was a popular impression of the rise of the far right, and the danger of that- machismo, racism, xenophobia,” Javitxu explained. “In that protest there were a lot of people who weren’t in formal political movements,” he continued, including himself among their number. Javtixu said he had previously been in the Podemos party in 2018, and had left-wing views, but that he wasn’t really organised at that point. In all, 200 young anti-fascists protested against Vox on the 17th, facing violent attacks from the police in the process.

After the demonstration was over, six young people, four adults and two minors, all of them under 24 years of age, were arrested at random in the surrounding area. The police made their choices based on the look of their targets’ clothing – indeed, one of the six did not even attend the anti-Vox protest. Four of the six, Javitxu alongside them, were detained when police entered a bar close to the site of the demonstration. In Javitxu’s case, he simply saw a minor being arrested in the bar, and when he tried to point this out to the police officer and tell him to be careful, he was grabbed and detained too. He asked the officers why he was being arrested, but didn’t get much of a response: “Their only answer was that I was in the protest, so maybe I had done something.” This was an arrest on pure suspicion, on assumed guilt.

And the crimes for which this haphazard bunch of arrestees, one of whom wasn’t even present at a protest, stood accused? Public disorder, and assaulting a police officer. These were the charges on which the Z6 faced trial in the Provincial Court of Zaragoza, with a sentence of six years in prison for the four adults, one year of probation for the two minors, and a fine of €11,000 being handed down in January 2021. This conviction was, however, based on the sole evidence of the testimony of the police officers, with witnesses and evidence that could prove the innocence of the Z6 being ignored. Crucially, security footage caught by University of Zaragoza CCTV cameras shows the violence at the protest, but the footage does not show any of the Z6 involved in fights with the police at any point. However, this footage was not admitted as evidence by the judge.

Following the initial judgment, the sentence was then increased by the High Court of Justice of Aragon to seven years for the four adults in October 2021. Javitxu explained that a sentence of this length for anti-fascist activism is unheard of; typically, arrested anti-fascists receive sentences of two or three years. The Z6 appealed this decision to the supreme court, and the appeal process dragged on with no decision until this year, when the supreme court finally decided on the aforementioned sentence of four years and nine months, plus fines. Even if the jail-time has been reduced, the fact that innocent anti-fascists are being imprisoned at all is a tremendous blow to the left, and a victory for both the far right and the repressive apparatus of the state.

“Francoism never went away. There is no real democracy in Spain.”

Beyond the police narrative of events, I wanted to get Javitxu’s perspective on the reasons for the arrests and the sentences, and to discuss the significance of the criminalisation of his and his co-defendants’ political activity. In Javitxu’s opinion, “they want us in jail because we have a problem with police hierarchy and far-right movements. They are linked.” Indeed, Javitxu contends that the police are very close to far-right movements in the Spanish state. Furthermore, he feels that the Z6 have been hit with such heavy jail-time specifically to send a message to other protest movements. Javitxu pointed out that the protest in 2019 was the first anti-fascist protest he had seen in Zaragoza with new people who weren’t just part of the pre-existing movements of the left, fresh people who saw a danger in far-right ideas – and of course, fresh layers of society taking part in protests is dangerous to the status quo, dangerous to the capitalist state. Adding to this, Javitxu outlined a repressive wave in motion throughout the Spanish state in recent years, with the arrest of the Catalan rapper Pablo Hasel for criticism of the monarchy serving as a prime example.

Javitxu dates this repressive wave from late 2017 and the state backlash against Catalan independence referendum. He argues that the Spanish government is afraid of the number of people who took to the streets to fight for Catalan independence, and that it wants to try and clamp down on future mass movements. In the context of this, abnormally harsh sentences for protesters opposing the far right appear as a weapon for dispersing and defusing a protest movement before it can cohere. Indeed, when I spoke of the courts as a capitalist class weapon, Javitxu agreed with me. “Francoism never went away. There is no real democracy in Spain.”

The situation now is bleak. This means that the question of how the movement fights back against the convictions is crucial, so I naturally wanted to know what Javitxu thought about the issue. His answer was keeping up pressure, continuing the fight: “If you want to stop the repressive machine in, for example, the housing movement, and the bank are going to throw you out of your house, then there must be a movement to avoid the eviction. So if you want to end the repression of this movement, you need to stop more evictions. If you want to stop the repression of the workers’ movement, you need to strike more, protest more.”

For Javitxu, there is no solid border between the struggle in the courts and in the streets – indeed, for him the question of liberty is a political one, which requires an organised response. “I think if you want to fight back against repression, you need more of a political movement.” He pointed to the example of the Z6 solidarity campaign so far, which has gathered the support of the political parties, trade unions and movements of the left, as well as musicians and actors, and which has continued to protest and agitate for a total amnesty.

Of course, with the dire turn events have taken, the need for a political support campaign has only deepened, as has the necessity of internationalising the campaign and getting support from workers’ and popular movements across the world. If pressure can be brought to bear on the Spanish government on multiple fronts, it will be to the benefit of the Z6.

The question of the movement’s response naturally entails another: What next for the anti-fascist movement in the Spanish state? Javitxu felt that the main problem of anti-fascism currently is that “there are not enough people involved. The anti-fascist movement needs to do more to influence popular opinion.” He also pointed out a problem with how the anti-fascist movement has traditionally operated: “I think there are people that still think the far right are just skinhead Nazis who are in the streets with knives and so on. It’s really different, the way the far right are organising themselves right now. There are Nazis with a skinhead aesthetic, but they are not the majority of the far-right movement right now. They are not the imminent danger. Vox for example, I think there is a difference in how they do politics.”

Javitxu pointed out that while Vox might hate groups like LGBT people and immigrants, the party is much more careful in how it expresses its ideas about these groups. It does not call for violence openly in the way a neo-Nazi gang would, but rather Vox seeks to influence and sway public opinion, to bring in parts of the traditional conservative voter base. In Javitxu’s view, the anti-fascist movement needs to find a way to combat this more “official” form of fascism. This dilemma is reminiscent of our own situation here in Scotland and the wider UK, where our anti-fascists may be able to outnumber and kick the fascists out of towns and cities on a good day, but where far-right ideas spur government policy regardless and receive silence, or even approval, from the Labour Party.

I ended our call by asking what the Scottish workers’ movement can do to support the Z6. Javitxu felt that the best way for people in Scotland to support the Z6 is, first and foremost, to spread the word: “It’s really important at the moment for this to be known about.” The campaign for an amnesty for the prisoners will be continuing, so Scottish workers need to keep up to date and show solidarity where they can. If you can bring up the cause of the Z6 in your trade union and organisational branch meetings and encourage them to contact the campaign and get involved, then please do so. And of course, there is currently a fundraiser to cover both the fines and the legal costs of the Z6 case. Please donate if you can, and spread it in your groups and networks.

Javitxu also wanted to underline to my readers that “if they know someone who is in some kind of trial, not to let him or her fight this alone. The most important support they can give to any victim of repression is emotional support.” We have cases here in Scotland that are in need of this kind of comradeship, like the Starmer Two, a pair of Palestine protesters arrested for demonstrating against Keir Starmer in December last year. Comrades bearing the brunt of police repression could always use a friend and a helping hand.

When we raise the call of freedom for the Zaragoza Six, the old struggles live anew in our words. We remember the names of friends and martyrs, class war prisoners old and new: John Maclean, Nicola Sacco, Bartolomeo Vanzetti, George Jackson, Angela Davis, Abdullah Öcalan. We remember the love, hope, rage and solidarity that fired, and fires, hearts in streets all across the world in cause of their liberty. And we fondly recall the words of the great American socialist Eugene Debs, another victim of capitalist persecution, who said: “While there is a lower class I am of it, while there is a criminal class I am of it, while there is a soul in prison I am not free.”

As for Javitxu himself, he remains defiant. Throughout our conversation he was adamant that he will continue to participate in anti-repression movements, and that his experience with the courts has only made him firmer in his resolve. He wants to show others what the judicial system does to people, and to express himself to others who are facing repression from the state.

“I had passed from a lot of states of depression because of this. I think that these are thoughts that are normal. After the second trial, I really wanted to abandon social movements, to go away, to disappear. And it’s this that they want. They want us to surrender, give up, and not to fight for a better world, a better situation for our comrades, friends, family. I think if someone is living this kind of thing, like trials for fighting for a better world, maybe, maybe, they are on the right side of history. I did nothing wrong, my conscience is peaceful. For now, I have no problems. If I go to jail, it will be years to study politics, to form myself, to be a better militant for the movement, to change this shit, this judicial system, this political system.”

All that remains to be said is that Javitxu Aijon and the Zaragoza Six are comrades in need. They deserve our support and assistance.

For them, for all political prisoners – tenacity, courage and fury!

Free the Zaragoza Six!

You can keep in touch with the Z6 campaign at these links:

- Fundraiser campaign for the Z6.

- Campaign email address: contacto@libertad6dezaragoza.info

- The campaign’s website has a manifesto with a section for signatures from supporters at the bottom of the page.

Originally published at: https://heckle.scot/2024/04/anti-fascists-demand-freedom-for-zaragoza-six/

Heckle is an 0nline Scottish publication overseen by a seven-person editorial board elected by members of the Republican Socialist Platform.

To join the Republican Socialist Platform, visit: https://join.republicansocialists.scot/

Photos from Heckle.Scot

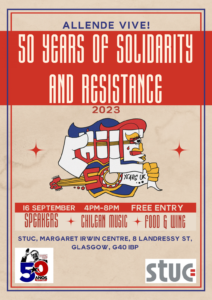

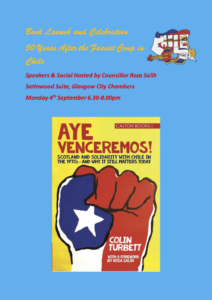

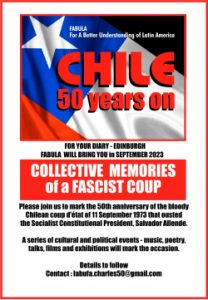

Programme still in development for September 2023 with participation of FABULA ( For A Better Understanding of Latin America ) Full details here:

Programme still in development for September 2023 with participation of FABULA ( For A Better Understanding of Latin America ) Full details here: